During the first flickering of life on earth, ribonucleic acid (RNA) occupied center stage. Since its shadowy beginnings, RNA has become a basic constituent of all living cells, faithfully transcribing DNA messages contained in genes and translating these into proteins.

Now, Alex Green and his group at ASU’s Biodesign Institute and scientists from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Northwestern University, along with a group of international colleagues are carrying RNA’s startling capacities a step further.

In this animation, Wyss Institute Postdoctoral Fellow Alex Green, Ph.D., the lead author of “Toehold Switches: De–Novo–Designed Regulators of Gene Expression”, narrates a step–by–step guide to the mechanism of the synthetic toehold switch gene regulator. Green is currently a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Molecular Design and Biomimetics and ASU’s School of Molecular Sciences.

Alex Green, formerly with the Wyss Institute, Harvard, is a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Molecular Design and Biomimetics and ASU’s School of Molecular Sciences.

Dr. Green is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow in Computational & Evolutionary Molecular Biology (2017) and the recipient of an NIH New Innovator Award (2017), a DARPA Young Faculty Award (2017), and an Arizona Biomedical Research Commission New Investigator Award (2017).

(Photo Credit: Arizona State University)

November 4, 2019

In a new study, they describe methods for designing sophisticated RNA circuits, which can perform a variety of computer-like logic tasks within living cells. Advancing previous efforts in the engineering of RNA switches, the new work demonstrates two clever designs capable of sensing inputs and turning off gene expression.

“This study is an extension of the work that we published in 2017, where we showed that we could use RNA molecules engineered from scratch to carry out complex logic decisions inside cells,” Green says.

The group’s findings appear in the advanced online edition of the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

In recent years, RNA’s remarkable versatility has been appropriated by synthetic biologists and cajoled into performing new tasks under human design. By turning RNA-based structures into tiny logic circuits, researchers are beginning to adapt the ancient molecule for a range of beneficial uses.

The ability to intervene and fine-tune or even redesign the machinery of life opens exciting new avenues in chemical synthesis, intelligent drug design, energy production, environmental remediation, next-generation diagnostics, regenerative medicine and cancer therapy.

The simplicity and versatility of RNA, composed of just 4 nucleotide letters (A, G ,C and U), make it an ideal platform for programming, information processing, computation, and control functions.

Gaining a toehold

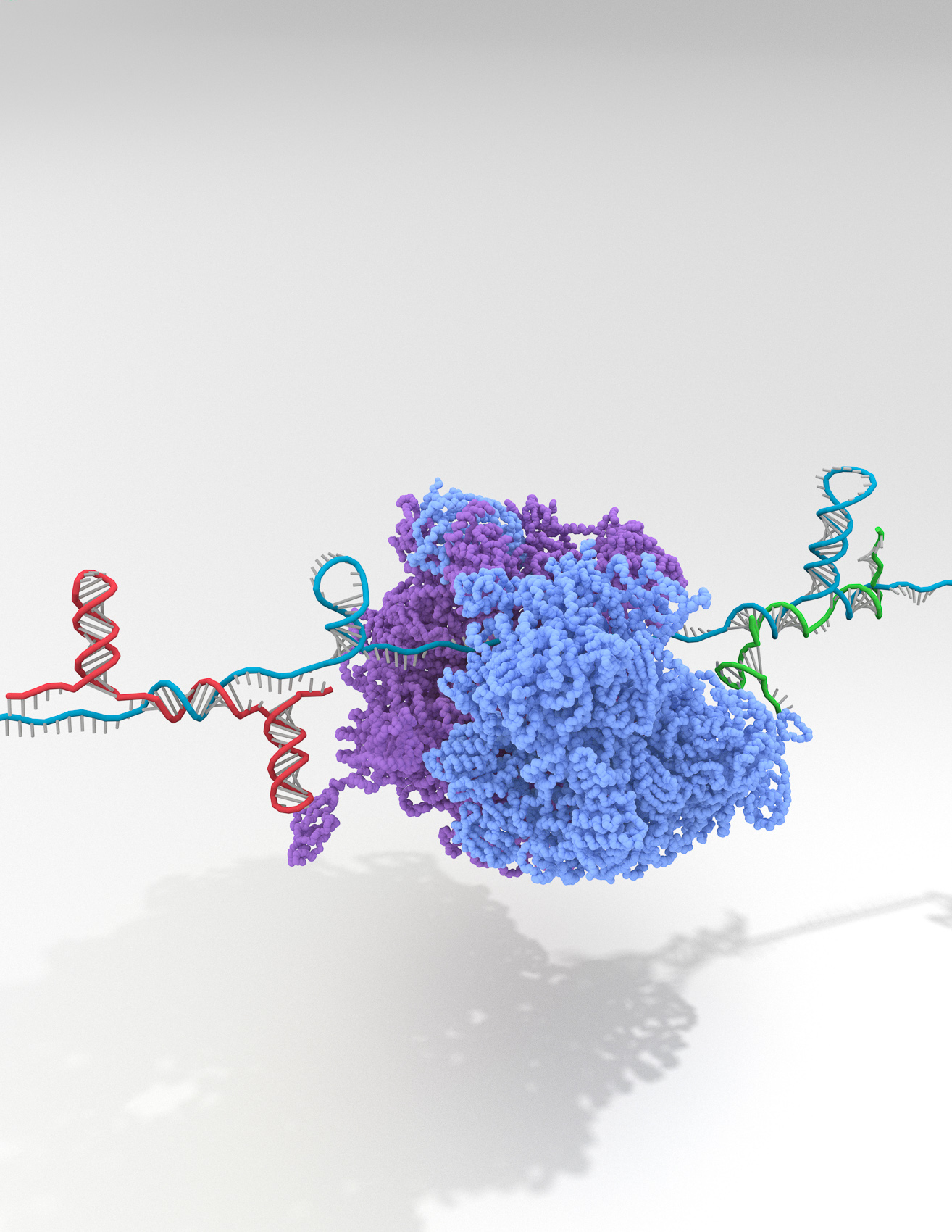

This illustration shows how a complex synthetic RNA containing multiple programmable Riborepressors (long teal blue strand) is bound by incoming trigger RNAs (shorter red and green RNA strands) that change the Riborepressors’ secondary structures to block the protein-synthesizing ribosome from accessing its binding sites (purple and light blue structure in the center). Credit: Alexander Green / Arizona State University

The technique described in the new study takes advantage of the fact that RNA, unlike DNA, is single-stranded when produced in cells. This fact allows researchers to computer-design RNA circuits that can be activated when a complementary RNA trigger strand binds with an exposed RNA sequence in the circuit. The binding of complementary strands is regular and predictable, with A nucleotides always pairing with U and C always pairing with G.

Riboswitches were first uncovered in natural systems, where they act to alter genetic activity in response to environmental cues. They are believed to play a vital role in maintaining cell homeostasis, among other functions. Usually, riboswitches perform their regulatory activities by binding a target metabolite, which causes a change in secondary structure conformation, resulting in modification of gene expression.

Synthetic RNA switches are composed of two primary components: a sensor domain that detects signals within a cell and an actuator domain that regulates gene expression. One of the advantages of RNA switches is their modularity, which allows them to be combined in various ways and adapted for complex functions.

Green and his colleagues have worked on a variety of RNA circuits using a device known as a toehold switch. It is composed from an RNA sequence that encodes the gene for a particular protein of interest. In order for the RNA circuit to successfully express a gene, the cell’s translation machinery must be able to access and read the gene sequence at a location along the RNA known as the ribosome binding site (RBS).

Variations on the concept of a toehold switch rely on designing RNA structures that are activated by a complementary trigger stand, that fuses with an exposed RNA segment. In order for the RNA-encoded gene to be expressed and a protein product produced, the translation mechanism must have access to the RBS. Toehold switches act by hiding or exposing the RBS within a hairpin-shaped structure.

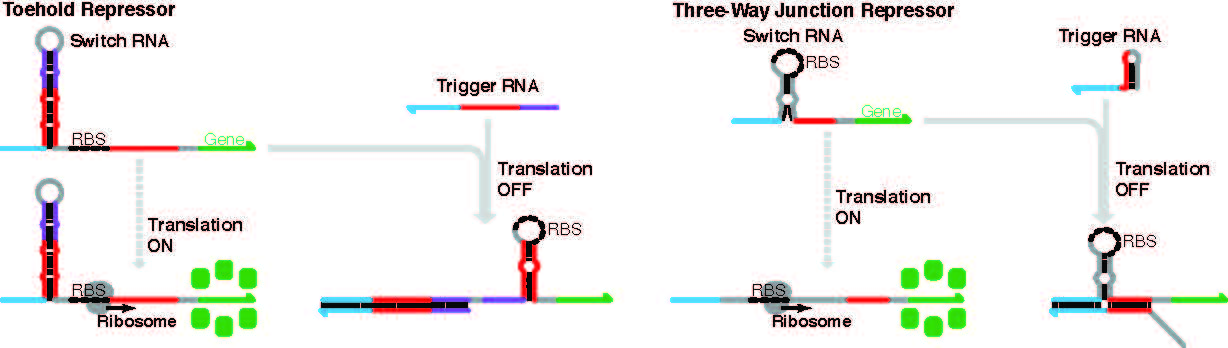

When the complementary trigger strand binds with the toehold switch, the RBS either becomes available, facilitating protein translation (as seen in the accompanying video) or the opposite happens. In the former case, the trigger strand binds with and activates the switch, but now, the RNA structure changes shape to sequester the RBS and shut off protein translation of the gene. (Fig. 1 shows the two kinds of gene repressors outlined in the current study.)

Highly targeted gene regulation of this kind could have far-reaching applications, for example, for shutting down aberrant disease genes, blocking viral replication or ramping up immune function for immunotherapy.

Ceaseless repression.

The graphic shows two types of gene repression systems constructed from RNA. Each relies on the engineered structure’s ability to shut off gene expression by sequestering the ribosome binding site or RBS to block translation into protein from occurring. When a complementary trigger strand binds with either a toehold repressor or a three-way junction repressor, the hairpin-shaped structure undergoes a conformational change to shelter the RBS from the cell’s machinery of translation. Repressor devices like these can be combined in sophisticated ways to allow combinations of input messages to affect the eventual output. (Credit: Arizona State University Article)

Living logic

In the current study, which was led by Green and Peng Yin of Harvard, two types of RNA gene repressors are described, known as toehold repressors and three-way junction repressors. The new work advances the field with fancier designs that can act as logic gates for switching functions on and off according to multiple RNA inputs. These circuits were developed by study co-first authors Jongmin Kim and Yu Zhou.

Specifically, so-called NOR and NAND gates were designed and their gene suppressing abilities tested in Escherichia coli bacteria. Such circuits are referred to as universal logic gates, because combining them in various ways can produce any form of digital logic.

A two-input NAND circuit will produce an output—in this case, gene suppression—only when both input channels are triggered. A two input NOR gate will block gene expression of the protein if either input is triggered or if both inputs are triggered. The study demonstrated that multi-input gene repressors of this type could successfully produce a 160-fold reduction in gene expression.

A method of high-throughput RNA structure probing known as SHAPE-seq was used to verify that the described circuits, built from scratch, were indeed active in bacterial cells. This was the first time such RNA circuits have been validated in this way, work carried out by study co-authors Paul Carlson and Julius Lucks.

A key advantage of the current suite of RNA regulatory circuits is their high degree of orthogonality. This refers to engineered biological structures that are so dissimilar to their analogs in nature that they can only interact with them to a very limited extent, if at all.

Likewise, the circuits are engineered not to interact with each other, except where specifically designed to do so. This makes such artificial regulators highly specific and non-overlapping in their activities and capable of regulating different stages in a synthetic gene network with high specificity.

This is an important advance, as interfering cross talk between various modular RNA repressing components has been a limiting factor up until now. The newly-designed three-way junction repressors are particularly orthogonal and therefore useful for complex, combined circuits, enabling up to 15 devices to operate in tandem. (The 3WJs were designed by co-author Yu Zhou, currently a postdoc in professor Green’s lab.)

Future cell circuitry

In recent studies, Green and his colleagues demonstrated the power of the toehold methodology to produce accurate, inexpensive, paper-based diagnostics for diseases including Zika and Norovirus. The current research will enhance such efforts, expanding the range of sensitivities and analyte detections possible. Cell-free approaches of this kind are particularly attractive for diagnoses of emerging threats and during disease outbreaks in the developing world, where medical resources and personnel may be severely limited.

“The end goal of all of this is to develop tools that will enable us to program cells and biological systems in the manner that we program computers,” Green says. Given the vast diversity of materials created naturally by cells, from medicinal plant byproducts to hardwoods, the possibilities are broad. For example, cells could be induced to make easily biodegradable plastics, using green chemistry, obviating the use of oil in plastics production. “I think that’s the future of biotechnology and sustainable living on this planet.”

De-Novo-Designed Translation-Repressing Riboregulators for Multi-Input Cellular Logic

Jongmin Kim, Yu Zhou, Paul D. Carlson, Mario Teichmann, Soma Chaudhary, Friedrich C. Simmel, Pamela A. Silver, James J. Collins, Julius B. Lucks, Peng Yin1, Alexander A. Green

The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University (www.biodesign.asu.edu) integrates leading-edge research in biology, engineering and computer science to address challenging problems posed by disease, depletion of natural resources and threats to security. Understanding and emulating nature is essential to solving these problems and is the unifying thread in the highly diverse research of the institute. The collaborative structure of Biodesign is designed to accelerate discoveries and translate them into real-world applications in health care, engineering and environmental sustainability. For information, visit

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University (http://wyss.harvard.edu) uses Nature’s design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing that are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and formation of new startups. The Wyss Institute creates transformative technological breakthroughs by engaging in high risk research, and crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers, working as an alliance that includes Harvard’s Schools of Medicine, Engineering, Arts & Sciences and Design, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, University of Zurich and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Harvard Medical School (http://hms.harvard.edu) has more than 7,500 full–time faculty working in 11 academic departments located at the School’s Boston campus or in one of 47 hospital–based clinical departments at 16 Harvard–affiliated teaching hospitals and research institutes. Those affiliates include Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Hebrew Senior Life, Joslin Diabetes Center, Judge Baker Children’s Center, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Massachusetts General Hospital, McLean Hospital, Mount Auburn Hospital, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and VA Boston Healthcare System.

Written by: richard harth

The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University

Source: https://biodesign.asu.edu/news/%E2%80%99s-switch-synthetic-circuits-regulate-gene-expression